A Trauma-Informed Perspective on Restraint Reduction

Dr Brodie Paterson is an experienced practitioner, researcher, and expert witness with degrees in psychology, education and social policy and has published more than a hundred papers, book chapters and research reports. He is currently Clinical Director of CALM Training, a specialist consultancy, support, and training provider to services supporting people whose distress may present as behaviour that challenges.

In a guest blog for SCLD, Brodie shares his own perspective on how trauma can inform Restraint Reduction…

“Any discussion around the idea of restraint reduction must start by acknowledging its long history. Concerns over the misuse of restraint and coercion with regards to vulnerable children and adults can be traced back a very long way; indeed, a non-restraint movement flourished in the 18th century with asylum reformers calling for ‘moral management’ involving kindness and compassion to replace coercion.

I too have a long history with restraint. I originally trained as a mental health and learning disability nurse in the 1970s, before going on to further studies; I witnessed the misuse of major tranquilizers, seclusion, and physical restraint in a number of institutions and did not do enough to prevent it. Ultimately, it was only when I was in charge of a service and trying to change what was a toxic and corrupted culture into a therapeutic environment, that I felt sufficiently empowered to try to reduce the use of restraint and seclusion and to question why it was being used.

This led to me to discovering that restraint could have fatal consequences in certain circumstances and to undertake my own research that found staff were most at risk of suffering a serious injury when they were attempting restraint.

The psychological consequences of restraint were self-evident. It could and did traumatise and retraumatise those restrained, those involved in undertaking the restraint and those who witnessed it. Consequently, reducing or eliminating restraint struck me then, as it does now, as something of ‘no brainer’.

The psychological consequences of restraint were self-evident. It could and did traumatise and retraumatise those restrained, those involved in undertaking the restraint and those who witnessed it.

My interest in how to avoid restraint led me first to explore the role of de-escalation, i.e., what staff should do when service users were in crisis to avert violence, then to evaluate the impact of training and ultimately to what are described as ‘whole organisation public health whole- based approaches’. ‘Whole organisation’ in this context meaning that every element of the organisation, such as its culture, values, policies care model and procedures, must explicitly support the reduction of restraint. In practice, whole-organisation public health-based approaches challenge attributions which locate the responsibility for violence in factors ‘within’ the person such as their bad character, bad choices, or diagnosis, focusing instead on what has happened and is happening to the person. They seek to identify and address the root causes of the use of restraint to prevent it.

Such approaches are actually compatible with a number of practice models including recovery and some applications of Positive Behaviour Support. However, recent developments in how we understand trauma have led to calls that services supporting children and adults whose distress may present in ways that services find challenging to prevent, should be ‘trauma-informed’. In practice this means they need to understand what trauma is and how it may impact individuals, families, and communities, but also individual workers, staff teams and organisations set up to provide education, care, and treatment.

How trauma is understood has evolved over time. Current thinking would suggest it is best thought of as an experience or experiences (including relationships) that have overwhelmed the individuals internal coping strategies (their personal resilience) and their external coping strategies (the safety, co-regulation, and stability that our connections with others may provide) and resulted in persistent cognitive, emotional, behavioural, or relational problems that cause significant distress.

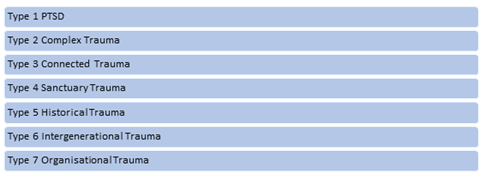

Trauma may happen to individuals, but it may also happen to groups of individuals and communities who may be affected by trauma, linked to racism, misogyny, or economic exclusion for example. The impact of trauma may be historical e.g., in the legacy of colonialism or of rapid de-industrialisation in the case of economically excluded individuals and groups. In these cases, trauma can also be intergenerational. Sadly, sometimes the source of trauma may be in the services set up to educate, care or treat the vulnerable child or adult. This is called ‘sanctuary trauma’. (See Figure 1 below).

Figure 1. (adapted from Paterson et al 2018)

Paterson B., Young J and Bradley P. Recognising and responding to trauma in the implementation of

PBS? International Journal of Positive Behavioural Support, 7(1) 4-14(11) 2017.

It is not enough to realise the collective impact of trauma – we need to learn how to recognise its effects and begin to develop responses which adopt the core principles of trauma informed practice. These are safety, choice, collaboration, trustworthiness, and empowerment.

We need to actively avoid re-traumatisation (so avoiding the misuse of power which may include restraint) understand what has happened to the individual, how they have experienced these events and what effects experiencing trauma has had in the short and long term.

Many people impacted by trauma struggle with emotional, and consequently, behavioural regulation. Hyper-vigilance and hyperarousal are normal responses to the presence of a threat but can become embedded in the individuals psyche even after the threat is removed. Complex trauma often involves not only repeated abuse, but also neglect, where the empathic, attuned relationships we need to have consistently available to scaffold our developing cognitive regulatory abilities are absent. The combined effect may leave children and adults struggling to stay within the window of regulation in which they can empathise, reflect, learn, and remember. (See Figure 2 below).

Figure 2.

Children who are neurologically atypical or who have particular sensory needs may also struggle with emotional and behavioural regulation with what may be reduced internal and external coping resources, meaning they are more readily overwhelmed and thus traumatised.

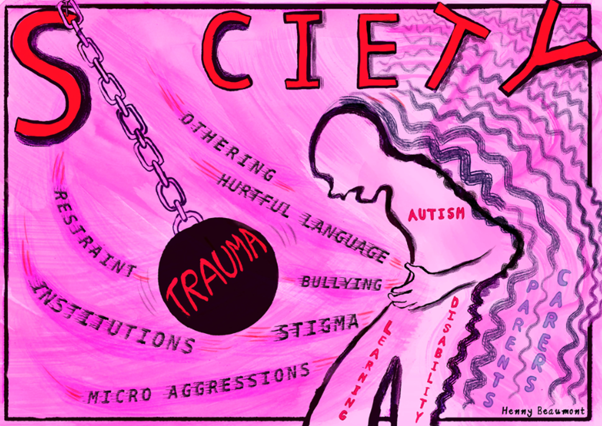

What all of this means is that we need to think about how we develop supports for individuals. Such support must recognise that the root causes of the distress which present as ‘challenging behaviour’, or that staff may interpret as wilfully ‘bad’, ‘attention seeking’ or ‘manipulative’, is in fact none of these things and such language should no longer be used in understanding the child or adult’s trauma.

Figure 3. Original Artwork by Henny Beaumont 2 .

Our job is to develop and design services that help people to feel safe and enable them stay within their window of tolerance for long enough to start to develop the connections and relationships with others that form the basis of future emotional and behavioural regulation. You can’t punish an emotionally dysregulated child or adult into becoming behaviourally regulated. At the level of the individual this should involve an integrative functional assessment and the development of an individualised support plan.

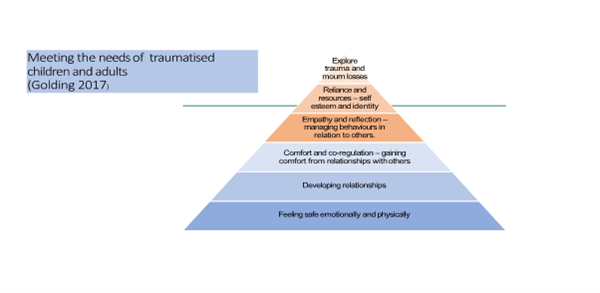

Figure 4. Golding and Hughes (2012) meeting the needs of traumatised children and adults with a learning disability.

If we can deliver individualised supports designed to enable the individual to stay within their window of regulation and gradually widen that window to develop their resilience, we can avert the crises that are so often associated with restraint. We can give staff an alternative narrative that reframes ‘challenging behaviour’ as an indicator of distress to which we must respond with compassionate inquiry and empathy, not punishment.

Unfortunately, what continues to happen in some settings are scenarios where we attempt to fit people who are impacted by trauma into services which are not trauma informed. The effect is akin to trying to fit a square peg into a round hole; it won’t fit and if in frustration we attempt to use force, we are likely to damage the peg and the board.

Trauma informed approaches don’t offer quick fixes to reducing restraint and there are many challenges to its successful implementation.

We need leadership teams who embrace and exemplify the approach; we need adequate resources in suitable buildings with appropriately trained staff; we need sustained, concerted action to address the potentially corrosive impact on staff wellbeing, of sustained engagement with children and adults who are struggling to regulate.

We need leadership teams who embrace and exemplify the approach; we need adequate resources in suitable buildings with appropriately trained staff; we need sustained, concerted action to address the potentially corrosive impact on staff wellbeing, of sustained engagement with children and adults who are struggling to regulate.

We seek to transition from physical to relational holding, in which our staff can be present to the distress of the child (rather than denying it or moving to punish the child) be empathic and sufficiently reflective to identify the impact of the behaviour on their own feeling and thinking, and at the same time identify and implement solutions to the cause of distress or provide a safe relationship where distress can be held.

To accomplish that transition we must support staff. Inadequate resources may cause burnout. Inadequate skilled support where the role requires empathy may cause compassion fatigue. Burnt out, emotionally exhausted staff can’t do trauma-informed care and the negative emotional responses which are ordinary responses to behaviour that challenges, may begin to determine how they respond – leading to the misuse of restraint.

We need real partnerships that put those with lived experience at the heart of how we design, implement, and evaluate services to ensure they are flexible, accessible, and robust. Trauma Informed Care is not a magic bullet; its implementation requires sustained action within our services, but also in our communities, to address the root causes of trauma which often lie within poverty, racism, misogyny, neglect, and abuse. The power of understanding trauma in transforming how we think and what we do as a result, is though truly unparalleled.”

Dr Brodie Paterson